IAN HUTCHISON

Career Summary

1949 : Born.

1965 : Trainee taxidermist at Rowland Ward Limited.

1967 : Carnegie Scholarship, training in taxidermy at British Museum (Natural History).

1968 : Employed by British Museum (Natural History) as a Scientific Assistant. Continued Carnegie Scholarship at Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh.

1969 : Continued Carnegie Scholarship at Alexander Koenig Museum in Bonn and Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt.

1974 : Promoted to Scientific Officer.

1981 : Promoted to Higher Scientific Officer.

1983 : Elected Chairman of the Guild of Taxidermists.

1991 : Made redundant and worked unpaid as a trainee gunsmith for Adam Davis.

1992-1995 : Self-employed Biological Model Maker / Engraver producing special effects for various film companies. During gaps in film work, I worked for Premier Yachts - painting, varnishing and fibreglassing. I also spent a season oyster fishing.

1995-2005 : Worked for IGG Component Technology as a Technician/Inspector - environmental testing and inspecting electronic components.

Aug-Oct 2005 : Worked for RBM Anodising – driving (towing 32 foot trailers), jigging and packing.

Dec-Feb 2005/2006 : Worked for Cherrytech – inspecting printed circuit boards; surface mount and through hole soldering.

2006-2009 : Worked for Rolls Royce Motor Cars (leather shop) – leather covering.

2009 : Retired.

These jobs working in industry taught me a lot, particularly about people and their attitudes to work. When I started at Rolls Royce, I was told by the boss: “There are 70 people working in this leather shop: a few are very good and a lot are fast, but you can count on the fingers of one hand those that are both!” That says it all!

Early Years

I was born in Newbold-upon-Avon in 1949 and was educated at Rugby (not ‘the’ Rugby School); this was just a primary school. At the age of 9, I moved to Rowlands Castle in Hampshire, a village north of Portsmouth.

I first became interested in taxidermy at the age of 12 when an older school friend who, having read a British Museum (Natural History) booklet on preparing cabinet skins made an unsuccessful attempt at skinning a blackbird. I thought it would be wonderful to be able to preserve such a beautiful creature, so he lent me the booklet and I too made the first of many unsuccessful attempts also on a blackbird. I soon became an avid collector of natural history specimens, mainly bird wings.

On a few occasions in my early teens, I would cycle 9 miles to Cumberland House Museum in Southsea where the curator, Miss Chambers, would let me read a copy of Practical Taxidermy by Montague Brown. Neither Miss Chambers or myself knew what wood wool was, so I continued my attempts at bird taxidermy using knitting wool assuming it was something similar. That was until I discovered the real thing! Although I could make cabinet skins, I was about 16 before I managed to get a starling standing on its feet. I also made attempts at skin mounting fish using ‘polyfilla’; they were a bit on the heavy side!

My form teacher, Mrs Vaile, was a biology teacher, but boys weren’t allowed to do biology in those days, so recognising my interest in taxidermy, she would let me stay after school and encouraged me in my early attempts at skinning birds. I remember trying to skin a male kestrel and a green woodpecker; I seem to remember having difficulty getting the skin over the head!

Also in my teens, I was a keen fisherman, but with access only to a couple of small local ponds and a short stretch of the very small River Ems. I mainly caught very small rudd and the odd small carp, which I would occasionally bring home in a bucket where my mum would let me put them in the bath so I could watch them. I would then have to take them all the way back to the pond to let them go again. I think this was the start of my interest in fish as living moving creatures rather than stiff static rigid trophies, although my early fish mounts were also rigid and lifeless.

From an early age, I knew I wanted to be a taxidermist and at the time, the only company taking on trainees was Rowland Ward Limited. So on leaving school at the age of 16 in 1965, I went to London to work at Rowland Ward Limited ostensibly as a trainee taxidermist under works manager, Mr Arthur Manning, who had told me at my interview I would be trained as a taxidermist. However, it soon became apparent I would not! I was employed on the ground floor at Leighton Place where the only taxidermy being done at the time was fox heads which were prepared by Bill Mathews. I became the skinner and after over 2 years, I was still only doing menial tasks such as balancing and polishing elephant tusks, unpacking crates, clearing blocked drains of rotting flesh (a quite frequent occurrence) and running errands. The closest I got to doing anything which could be classed as taxidermy was preparing the odd otter rudder (tail) or fox brush as a hunt trophy or eland (antelope) tail as a ‘fly switch’.

Fortunately, a friend of my father saw an article in the New Scientist about the Museums Association Carnigie scholarship in taxidermy. I applied in 1967 and won a place training at the British Museum (Natural History) where with Philip Howard, another Carnigie student, I was taught all aspects of taxidermy with Arthur Hayward teaching mammals, Ron Nash birds and Stuart Stammwitz plaster casting fish. The following year, the Museum employed me as a Scientific Assistant and I continued my scholarship for 3 months at the Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh where Willie Sterling taught mammals and John Murray birds. I was taught to cast and paint fibreglass fish by Steve McGonnigal who was highly regarded for his fish casting techniques which I subsequently modified and adapted to become the foundation on which I developed my own techniques.

Fortunately, a friend of my father saw an article in the New Scientist about the Museums Association Carnigie scholarship in taxidermy. I applied in 1967 and won a place training at the British Museum (Natural History) where with Philip Howard, another Carnigie student, I was taught all aspects of taxidermy with Arthur Hayward teaching mammals, Ron Nash birds and Stuart Stammwitz plaster casting fish. The following year, the Museum employed me as a Scientific Assistant and I continued my scholarship for 3 months at the Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh where Willie Sterling taught mammals and John Murray birds. I was taught to cast and paint fibreglass fish by Steve McGonnigal who was highly regarded for his fish casting techniques which I subsequently modified and adapted to become the foundation on which I developed my own techniques.

During the next year, I continued my scholarship spending time at the Alexander Koenig Museum in Bonn and the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt. I then continued my employment at the British Museum (Natural History).

During my first year at the Museum, much of my time was spent mounting birds for the British Bird Pavilion which was being refurbished. I was taught by Ron Nash who had himself been taught by a German taxidermist called Platt or Platts. The technique he used involved a central wood wool core of correct width across the shoulders and pelvic joints, and of the correct length between the two, but the core didn’t extend much beyond the pelvic joint. The femur was usually left attached to the leg and the humerus to the wing; they were then wired to the central core. The neck was formed of tow wrapped on a wire attached to the body and the tail was supported by a wire also fixed to the body core. The remainder of the body cavity was loose filled with chopped tow until hopefully a lifelike shape was achieved.

Although this technique could produce some reasonably good mounts in skilled hands, I later abandoned it in favour of a more conventional full body form of either wood wool or balsa wood.

One of the Museum’s ornithologists would look at my recently mounted birds and pass judgement on whether they were better than the existing specimens in the gallery, which they frequently were. Unfortunately, this led me to believe my work was of a higher standard than it actually was. At the time, I had no contact with other taxidermists and it was only by attending the early Guild meetings that I realised, after seeing the work of others, that my work could be a lot better!

In the early years of the Guild before anyone had gained sufficient credits to become professional members and act as judges, the committee would elect a panel of judges from members whose opinions they felt would be respected. Sometimes, I was one of those elected judges, so although some of my work may have had room for improvement, my opinions as a judge were obviously valued. I later became the fourth member to gain professional status and was frequently asked to act as a judge throughout my time with the Guild. This was a thankless task which often meant I missed many lectures and demonstrations; however, I felt it was an honour and a responsibility I gladly accepted always giving it my all.

Taxidermy at the British Museum (Natural History)

It may surprise people to know that in my 23 years working at the Museum, I did relatively little taxidermy. By referring to my diaries and from memory, I guestimate that I mounted 145 birds, 32 mammals, 21 fish, 6 crustaceans, one reptile and one amphibian, and painted 12 cetaceans.

The number is small because most of the galleries being worked on didn’t require any taxidermy. None of the following required more than one piece of taxidermy: Fossil Mammals, Human Biology, Insect Gallery and Anthropod Gallery. It was possible to spend 18 months or longer without doing any taxidermy at all. I recall spending 9 months, possibly longer, refurbishing specimens for Tring Museum, with all the travelling involved. There were usually between 7 and 9 model makers and taxidermists. The most taxidermists at any one time being 5, who also made models. I repainted the Blue Whale twice(!), and modelled a 25 foot high termite mound, deep sea fish, fossil cetaceans, insects and much more.

One of the main aspects of taxidermy which I found unsatisfactory were the problems associated with the shrinkage of anatomical features such as noses, hooves, birds feet, fish heads etc. Early taxidermy books describe methods of re-modelling shrunken anatomical features with wax or some other compound, sometimes to the extent of re-modelling a large percentage of a fish head. I thought it would make more sense to avoid the shrinkage in the first place. This is why many of my most innovative techniques were the outcome of trying to avoid shrinkage by moulding and casting those features.

The use of moulding and casting in taxidermy has a long history even with the use of gelatine to make flexible moulds many years before the invention of silicone rubbers. Some outstanding work has been done in the past particularly on reptiles and amphibians. I have seen beautiful snakes and lizards cast in copper and bronze allowing the metal surface to become part of the coloured finish.

However, the way I adopted the moulding and casting of mammalian and avian anatomical features only became a viable technique due to the invention of cyanoacrylic “Super Glue” in the 1970s I think? By applying it one drop at a time, it became possible to glue the skin to the cast hoof of a deer or around the cast nose of a badger. Other glues were too slow drying or were too difficult to use. At the request of Guild members, many of my lectures and technical articles were on this subject.

Examples of work featuring these techniques include horse and deer hooves, badgers noses, duck and penguin feet, and a beaver tail all cast in either glass reinforced plastic or dental acrylic. The technique has been adopted mainly in America to produce artificial waterfowl heads.

Other techniques I developed which to my knowledge weren’t in general use at the time were the bending of the primary feathers of flying birds with the use of steam. I would also occasionally make my own eyes out of thin Perspex sheet by heating it and forming it. The reason for doing this was because in many eyes, particularly those of birds, the pigmentation is very close to the surface and no commercial glass eyes showed the characteristic.

My Approach to Fish

I have often been called a fish specialist, but in my opinion, I only give the same amount of attention and care to fish as I would to any other animal. That is, I try to portray them as living creatures in their natural environment.

Historically, fish were often mounted as trophies and whether a skin mount or a plaster cast, they were almost always displayed showing only the best side which had not been damaged by an incision or, in the case of a cast, some other damage.

The fins of skin mounted fish become rigid and fragile, and many areas of the head become shrunken and distorted. This is why I choose to mould and cast fish.

Many fish are soft floppy creatures when out of water and are very prone to distortion during the moulding process. To minimise any potential distortion, I developed a technique fixing fish in a natural swimming position in formalin prior to moulding (see prize winning technical article ‘Fixing Fish in Formalin Prior to Moulding’ in the Guild Journal No. 10 of December 1982).

I used this technique on a grayling cast in the round and supported on a worm in its mouth. In 1984, I attended a Texas Taxidermy Association conference in Houston as a guest of Brent Branham where my grayling won a first place ribbon. I left my grayling with Brent as an example of my work.

I feel the unpainted brown trout cast in the round which Pat Morris mentions in his tribute to me is my most innovative piece of work because it incorporates two or three techniques I developed for use on earlier fish. As Pat mentions, the fins were removed, but before they were removed, the fish with all its fins still attached was fixed in formalin with each fin fixed in a natural swimming position. I then made a two piece silicone rubber mould of each fin while it was still attached to the fish, which meant that the joint between the fin root and the fish body would be a perfect match requiring no filler or fettling. I then moulded the fish as described by Pat. The fish was originally exhibited supported by its nose breaking the surface of a Perspex sheet of water about to take a fly.

The significance of the smaller trout mentioned by Pat Morris is that it was my first fibreglass fish done under the tuition of Steve McGonnigal at the Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh in 1968. Although as piece of work it is well executed, I would not be pleased with it today as it has flat vacuum formed plastic fins; however it marked the beginning of the evolution of my fish mounting techniques, which is why I gave it to Pat.

Notable Projects

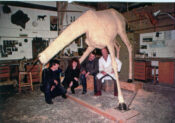

Many people consider my galloping horse supported on one foreleg to be my most notable project. However, although the horse is spectacular, I feel my brown trout and my grayling both cast in the round were more innovative and creative in their conception and construction.

There is though one aspect of the way I supported the horse that I am particularly pleased with. It appears to be supported on one leg, but is actually supported by its weight bearing on its back.

The square section steel supporting tube is shaped like a number seven, thus 7. The shorter horizontal arm was bonded in position inside the hollow fibreglass manikin about halfway along its back. The longer arm runs down inside the foreleg and is not bonded to the leg and is free to move, merely being held in position by foam rubber pads. The tube exits through the bottom of the hoof via a hole of a larger dimension than itself.

The purpose of doing this was to avoid the possibility of the leg breaking if the horse was to receive a knock when it was bolted down to the base of the display case.

Committee Work, Lectures, Demonstrations etc

23.3.1979 : Symposium at Nottingham University – lecture on Fish Casting & Fish Cast Painting.

1980 : Committee Member

28.3.1980 : Conference at the University of Liverpool – slide lecture on Fish Casting & Painting.

4.10.1980 : Seminar at Birmingham Museum – panellist on “Ask the Panel” answering members’ taxidermy questions.

April 1981 : Journal article on “The Reproduction of Birds’ Feet by Moulding & Casting in Various Media”.

1981/82 : Chairman Elect

Represented the Guild as a speaker at the Museums Association Meeting on Wildlife and Countryside Act.

11.4.1981 : Conference at the University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne – demonstration on Moulding & Casting Fish

12.12.1981 : Autumn Seminar at Stoke on Trent Museum – demonstration on Moulding & Casting Birds’ Feet.

1982/83 : Chairman

19.7.1982 : Opening address at the Charles Waterton Bi-centenary near Wakefield.

Dec 1982 : Journal No. 10 - Forward and article on “Fixing Fish in Formalin Prior to Casting” for which I was awarded £20 prize for the Best Technical Article.

Aug 1983 : Journal No. 11 – Forward.

1983/4 : Immediate Past Chairman

8.10.1983 : Seminar at British Museum (Natural History) in Cricklewood – demonstration on Producing Artificial Snow & Ice.

14.4.1984 : Conference at the University of Nottingham – demonstration on Fibreglass Mould Construction.

July 1984 : Game Fair at Broadlands Hampshire – exhibited a cast grayling at the Guild’s stand.

1985 : Committee Member

20.4.1985 : Seminar at Liverpool Museum – demonstration on Casting Anatomical Features Prone to Shrinkage.

13.9.1985 : Conference at the University of Nottingham – demonstration on Moulding & Casting Fish in the Round.

1986 : Committee Member

27.9.1986 : Conference at York University – talk on Review of Improvements in Taxidermy in last 10 Years.

1987 : Honorary Secretary

26.9.1987 : Conference at the University of Liverpool – illustrated talk on Mounting a Horse in Full Gallop.

1988 : Honorary Secretary

1.10.1988 : Conference the University of Nottingham – illustrated talk on Fish Painting.

1989/90 : Honorary Secretary

I first became elected as a committee member in 1980 and continued to serve on the committee in various posts until 1990 when I retired as Honorary Secretary. I was elected Chairman for the year 1982/83. This was a responsibility I took very seriously and made every effort to perform my duty to the best of my ability.

There were however two occasions when due to an oversight by others, I was put in very difficult positions with very little time in which to act. They are a both worth relating because, with hindsight, they are quite amusing.

The first occasion was at the Charles Waterton Bi-centenary celebration near Wakefield, which although it wasn’t an official Guild event, it was held in association with the Guild. As chairman, I felt it was my duty to attend even though it was expensive, and anyway, I thought it would be interesting to learn about Charles Waterton as I knew nothing about him. On the eve of the event, I was at the bar relaxing after a very long and tiring car journey when just as the bar was closing, a friend happened to mention my opening address in the morning. I just laughed as I thought they were joking; they then showed me a copy of the program which showed I was scheduled to give a half hour opening speech in the morning. I was aghast, as due to an oversight, no one had asked me to give a speech and I hadn’t even been given a copy of the program! This put me in a very awkward position, as to not give a speech would reflect badly on the Guild and also on myself. The situation was exacerbated by some of Waterton’s relatives having come all the way from Australia to attend the event, but how would I be able to give a speech as I knew nothing about Charles Waterton? I had to do something quickly, so I asked Rosina Down if she would brief me on Waterton, which she agreed to do. I then spent the next hour and a half in her ‘campervan’ with her and her husband briefing me as I took notes. I then went to my room, wrote a speech and spent most of the night rehearsing it. By the morning, I was physically and mentally exhausted, but I successfully delivered the opening address without notes, which people seemed to think was fine. However, some people mistakenly deduced that I had spent all night at the bar as I looked much the worse for wear. If only they knew the truth!

On the second occasion, a meeting had been called with the Department of the Environment (DOE) and the Museums Association to resolve issues regarding the implementation of the Wildlife and Countryside Act. All interested parties had been invited to attend; this included all museums, universities and any other institutions with a biological/zoological collection. The meeting was to be held in the British Museum (Natural History) in the Conversazione Room. The day before the meeting, I received a phone call from the Guild Secretary to remind me it was taking place and ask if I would be able to attend, which I told him I would as I worked in the Museum and it only entailed me walking upstairs and through a gallery.

There was no agenda, but as it was the DOE who was responsible for formulating the Act, I thought I should introduce myself to whichever member of their staff who would be chairing the meeting. There were about 70 or 80 people all standing around chatting and as no one had been given name tags, I didn’t know who was who, so I asked the Guild Secretary to show me who was chairing the meeting. He turned to me and said: “Well, you are.” It was about 5 minutes before the meeting was due to start, and I was dismayed and quite annoyed! Through an oversight, no one had told me, or perhaps they hadn’t even considered the matter. It is very easy to assume the chairman knows what is going on, but he or she only knows if they are kept informed usually by the Secretary. The Guild has a bit of a reputation for somewhat causal meetings, but I didn’t want it happening when I was in the chair. To this day, I still can’t understand why the Guild was expected to provide a chairman, when in my opinion, that responsibility clearly lay with the DOE. I did step up and chair the meeting and after introducing myself, asked the representatives from the DOE to come forward and identify themselves, and I invited delegates to speak or ask questions through the chair, having first identified themselves. The meeting actually went very well with many issues being resolved and questions answered.

At the end of the meeting, I was approached by a lady who introduced herself by telling me her name and saying: “You don’t remember me, do you?” I apologised and said: “I’m sorry, I don’t recognise your name.” Then, looking at me very intently and with a bit of a tear in her eye, she said: “Perhaps you’d remember me better if I told you my maiden name was Chambers and I was the curator of Cumberland House Museum where you used to come and visit me as a school boy.” Needless to say, I was delighted to see her again and I too had a bit of a tear in my eye. She was very obviously so proud that the 14 year old schoolboy had become the Chairman of the Guild of Taxidermists working in the British Museum (Natural History) as a taxidermist, and she said so.

I remained a committee member until 1987 when I became Honorary Secretary until I retired from the Guild in 1990.

There were usually two or three committee meetings a year which were often held at Liverpool Museum. This entailed a 6 am start and round trip of over 400 miles. It was gone 9 pm by the time I got home. There was no internet or email then.

I also represented the Guild as a committee member of the Museums Association for a couple of years.

I also wrote letters to the Editor under various pseudonyms excluding ‘Kingfisher’.

Early Inspiration

During my early years at the Museum prior to the founding of the Guild, I had no contact with other taxidermists apart from my colleagues whose work was generally about on par with my own.

The people who taught me were engaged in making models for the fossil mammal gallery at the time and although my colleagues were capable of producing good work, what actually inspired me were the specimens on display in the museum galleries. Most of the specimens were of a low standard, but amongst the poor and mediocre specimens would be the odd gem of a very high standard. It was seeing all this poor quality work which inspired me to try and produce work to equal the best in the Museum.

In those days, good photographic reference was almost non-existent and any books with photographs of birds invariably showed them sitting on a nest, which was no use if you wanted to mount a bird standing, perching or feeding. Our sources of reference were the Collins Guide to Birds of Britain and Europe, and the Reader’s Digest Book of Birds. I later found out that the illustrations in the Reader’s Digest book were drawn from badly mounted specimens, which were themselves probably copied from a poor illustration in a book!

I soon came to the conclusion that rather than trying to copy another taxidermist’s work or an illustration in a book, I should try to emulate Mother Nature. With this in mind, I collected all the photographic reference I could find, which I usually found in magazines. Today, with the internet and Google, it is possible to find all the photographic reference one needs.

There were only two or three books on the subject and I generally found the text and illustrations appeared to be obfuscatory. I can even read some of those publications today and find them confusing!

Teaching/Training

The Museum was looking for an experienced taxidermist to teach us mammal taxidermy and on my recommendation, they employed Roy Hale from Rowland Ward Limited who then became my boss. It is therefore slightly ironic that I ended up teaching Roy bird taxidermy and also fish casting and painting. He seemed to really enjoy mounting birds and learned very quickly.

I also taught bird taxidermy to two or three members of the model making staff, but Barry Sutton was the only one to really show potential. He joined the taxidermy team and became a proficient taxidermist producing some nice work. He is now a successful professional wildlife sculptor.

The two most successful taxidermists I taught bird taxidermy were Derek Frampton and Emily Mayer who both came to visit me when they were still at school.

Derek was 13 or 14 at the time and came to see me about 4 or 5 times. He assimilated everything I taught him and the improvement in his bird mounts was remarkable. He was a very observant and attentive student, and I’m sure he would have been a brilliant taxidermist even without my help. I think Derek is an exceptional taxidermist and is one of the most successful people I know. I felt honoured when he asked me to assist him mount a giraffe when he was self-employed.

He has remained a lifelong friend and comes to visit me quite often. It gives me great pleasure to have been of some help to him.

I always felt it was as important to teach a student how to think as it was to just teach them a technique. Someone with an analytical enquiring mind will identify why they have made an error, and find a way of rectifying it and a strategy to avoid it happening again.

When people tell me I’m clever with my hands, I point out to them that it is my brain that controls my hands.

Taxidermy Pre Guild

The last time I attended a Guild function was a guest speaker at the 40th anniversary conference in 2016. One thing I noticed was how young many of the members were. With this in mind, I feel it might be of interest to those young members if I describe the attitudes of taxidermists and the status of taxidermy in the 1960s and 1970s prior to the founding of the Guild.

Firstly, there was no internet or mobile phones, which means there was no Google, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter or anything else which relies on the internet. So if you wanted to learn about taxidermy, you either had to read a book or try and find someone to teach you. Most books of any use were long out of print and the couple of books that weren’t, seemed to be deliberately misleading or at best, very confusing!

It is my experience that very few taxidermists would be prepared to show anyone any of their methods of working which many considered to be their trade secrets. In fact, if you were lucky enough to enter a taxidermist’s workshop or studio, the common response would be that they would cover up whatever they were working on and some would even cover up their tools and materials, because they guarded their methods of working and the materials they used very jealously. This was even the case if you worked in the same firm. In the 1960s at Rowland Wards, I would occasionally have to deliver a bird to Mr Alfred Banister, the bird man who had his own room on the top floor. If he heard me approaching, he would shut the door to give himself time to cover up his work and if I managed to approach without him hearing me, he would hurriedly hide whatever he was doing! Because I was keen to learn, I would sometimes ask him a question about bird taxidermy. The reply was always the same word for word: “I ain’t f***ing telling you nothing. Nine years, I was only allowed to sweep the floor before I even got to skin a bird. Why should I tell you anything?” Needless to say, I gave up asking. Even some of the mammal taxidermists on the second floor had a similar attitude and I was often rebutted with: “Yes, what is it lad? Go away. Haven’t you got any work to do?” All very sad!

I can’t speak for other museums and institutions, but at the British Museum (Natural History), we had very little contact with other museums and for no real reason.

Many materials which we take for granted today were relatively new at the time or had not been invented, or were not commercially available. Polyester and epoxy resins, fibreglass, silicone rubbers, polyurethane foam and dental acrylics were still being experimented with by taxidermists and model makers, although the palaeontologists at the Museum seemed to be more advanced in the use of these materials.

Taxidermy was in a state of isolation and stagnation with no communication taking place. It was against this background that the Guild was founded.

Some Thanks & Thoughts

There were members of the Guild who have produced work of a higher standard than my own; there are also many who have done considerably more for the benefit of the Guild. I therefore feel honoured to be included in the list of influential past members.

I do however recognise that it is not necessary to be the world’s best taxidermist in order to be considered a notable or influential one. Thank you.

I also most sincerely thank every person who has contributed in any way to the benefit of the Guild, no matter how small that contribution.

Although I am no longer a practising taxidermist or even a member of the Guild, I feel it is very important that we continue to remember and uphold the reasons the Guild was formed, viz. to raise the standard of taxidermy in the UK by the dissemination of information through holding seminars, delivering talks and demonstrations, also by publishing technical articles and information.

So, please try to remember the Guild is not just a club; it has a reason for existing.

Other Interests

My main interests are shooting and fishing. I’ve done coarse, sea and game fishing at different times and have had some interesting experiences, including getting a size 4 long shank ‘black chenille’ fly stuck in my eye whilst trout fishing and landing a 9lb 12oz carp on 1¾lb hook length whilst fishing for chub on the Western Rother! Not easy!

My shooting has primarily been wildfowling and I became chairman of Emsworth and District Wildfowling and Conservation Association and also represented wildfowling on the Chichester Harbour Conservancy Advisory Committee. I spent a few years regularly clay shooting and today, I mainly shoot pigeons and rabbits for crop protection with the occasional day at game. I quite often appeared in the shooting press and I briefly held the British record for American Brook trout with a fish of 2lb 1oz, but not for long enough for it to even get into the record book!

My other interests are many and varied but they have one thing in common, they all require a high degree of skill and dedication to achieve success. Some of these interests have been transient, for example, I spent about 18 months making and flying boomerangs, but I haven’t done it since probably because I’ve had a frozen shoulder.

Since my teens, I’ve played ukulele, banjo, guitar and harmonica, and sang mainly traditional American folk, bluegrass and blues, with some English, Irish and Scottish folk. My voice was trained by a music teacher and I sang in a male choir where I sang first bass or occasionally baritone. I was specially selected to sing solo a cappella, performing every night for two weeks before audiences in excess of 200 people.

I would regularly perform in pubs, both solo and as one half of a couple of duos, one with an ornithologist friend who played guitar and the other with my girlfriend who was a museum curator and had a beautiful voice.

I’ve played with The Dubliners, Dominic Behan and The Bachelors, all at their request. Well actually, I didn’t play with The Bachelors; they joined in with me quite often when I used to play in a pub called The Stage Door, which was opposite the stage door of the Victoria Palace in London where they were performing at the time.

In about 1978/9, I formed a band called The Butser Hillbillies which lasted about 7 or 8 years. We had 5 members and most of us could play more than one instrument to quite a high standard. I was the ‘front man’ or lead singer and also played banjo mainly as a backing or rhythm instrument. However, two of the others also played banjo, one having won a prize for his picking in America. The other instruments were guitar, fiddle, mandolin, double-bass and harmonica. We played locally most weekends in pubs and clubs. I still often get asked to perform; the last couple of times being a Classic American Automobile Club rally where I sat on a bale of straw in the back of a model T Ford pickup and played; the other was at Goodwood Women’s Institute Christmas party.

I made a new neck for my banjo in 1982 or 1983 out of a piece of walnut from a tree which grew behind my mum’s house. The finger board is ebony and is inlaid with hand cut mother of pearl which I cut from shells given to me by Kathy Wey, Keeper of Mollusca at the Museum. It was made to fit an existing aluminium banjo body, but I later had a wooden body made for it incorporating traditional commercial fittings.

Since visiting the Wallace Collection of fine arms, I have been in awe of intricate engraving and inlay on many guns, I realised that this work was obviously all done by the skilled hands of a human being, but it took a while before I came to the conclusion that as I too was a human being, I should with practice, be able to do similar work, if not quite to the same high standard. I have since applied this philosophy to most of my creative work.

On being made redundant at the Museum, I worked unpaid with Adam Davis, an ex Purdey stocker, who shared a workshop with other gunsmiths. I had already successfully restocked my own gun when I worked at the Museum and Adam said it would be considered to be in the top 25% of Purdey’s work. Adam taught me chequering, but only after I’d made the tools to do it with. Alex Wright, also ex Purdey, taught me finishing. In the stocking process, I had to make new screws or pins as gun makers call them, which needed engraving, so I asked Adam if he could get it done for me. He looked at me with a mischievous glint in his eye and said: “No, you’ve done everything else yourself so you can learn to engrave!” which is exactly what I did. It took me quite a while before I was good enough to do the screw heads, but I needed 18 months more practice before I engraved my first gun.

Restoring vintage British shotguns was to become a hobby of mine and more than once, I have had to make the tools to make the tools do a specific job!

I have utilised some of my gun making skills to go on and make various items or implements which although unrelated, seem to have certain characteristics of form and function in common. Many have an organic element which is joined precisely to a metallic mechanism. One example is a penknife with its rugged antler scales and the ice cold clean lines of its blade with the click clack of the mechanism, or the leather pouch of a shot flask terminating in a brass measuring spout. Sometimes, I would engrave a tool or instrument just for the practise.

Perhaps I should stop trying to describe these things and just let the pictures speak for themselves.

Shot Flask

A leather shot flask for a muzzel loading shot gun circa 1845. The badly worn and damaged pouch was replaced by me after much thought and experimentation to work out how to do it. I asked a saddlemaker and a glover, but neither would do it and neither knew how it was originally made!

Engraved Articles

Painting

In 2021, I painted a skien of White-fronted geese on my bedroom wall, partly because the wallpaper was falling off and with the restrictions imposed during the Covid pandemic, it gave me a project I could do indoors. It was also more interesting than hanging wallpaper.

I made 24 trips photographing geese as reference for the painting, plus many more taking pictures of barbed wire fences and Phragmites.

The painting is 5’ x 5’. Acrylic was used for the background with enamel being used for the detail. It took nearly seven months to complete, but I didn’t work every day, and only worked a couple of hours or less at a time.

On seeing the painting, many people asked me for a print, so I decided to issue a signed limited edition of 275 prints with an image size 22” x 22” and an overall size 25” x 26”.

I also donated a framed print to the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust at Arundel to commemorate the founding of the Wildfowl Trust and Sir Peter Scott’s early work, with the proceeds of any prints they sell going to their organisation.

Others

Wildlife photography has been an ongoing interest of mine for the last 35 years and since I retired, I find I am spending far more of my time doing it. Although it is something I do for my own satisfaction, I have provided all the bird photographs and many others for a book, Mud Pattens in the Morning – A History of Wildfowling in Chichester Harbour by Steven Borland. Also on several occasions, I have provided photographs of taxidermy and other subjects for publication.

During my career as a taxidermist, because of the position I held at the Museum, I sometimes appeared on television and featured on radio both in the UK and also in Europe. I also quite frequently featured in the national press and other publications. This has also been the case with both my music and my other interests which have appeared in various publications and magazines.

An Afterthought

An Afterthought

I have rarely been totally happy with any of my work, but then I have been called a perfectionist. Well I do pursue perfection, but it is in the knowledge that it is unattainable and while my finished work may not be perfect, it might end up being fairly good.

If I have managed to help and inspire a few people during my career, I feel it has all been worthwhile.

Ian Hutchison, 2020

Gallery of Other Taxidermy Work

Tribute by Pat Morris

This small trout was one of Ian's first fish. It was made from fibreglass in 1968 when the technique was relatively new. He went on to prepare many other fish, culminating (in his words) in producing the unpainted form here. This has no visible lines to indicate how it was cast. Normally, such a fish would be made in a two-part mould but there are no flash lines along its body. In fact, the fins were removed (as normal) and a flexible, reinforced, rubber jacket was made around the whole fish posterior to the opercula. From this, the body was in resin, laid down inside the mould. The head was cast separately and the join lies along the edge of the opercula. Ian's main pride lies in how he had made the fish.

Impressed by a model fish that Ian had made, I once asked him if he would do a fish for me as an example of modern techniques and materials. He never did but in 2004 he contacted me out of the blue, for the first time in over ten years, to say that he wanted to give me some of his work. He had evidently not forgotten my request after all and gave me the above trout (with another early trout and a widgeon he had mounted) on the understanding that they would be kept as archival material and properly protected from dust and damage.

Ian is a keen wildfowler and the wigeon is set up in a pose that reflects a typical feeding posture, not a typical 'stuffed duck' pose. It is mounted on a bind-up body, so well made that it is perfectly symmetrical either side of the mid-line. Bind-ups were a specialty of Rowland Ward Limited.