JOHN E. COOPER

Introduction

I am not a taxidermist but a veterinary surgeon - a specialist comparative, wildlife, and forensic pathologist. I have had a life-long interest in natural history and wildlife and was closely involved with the Guild of Taxidermists at its inception in 1976 and for some years after.

My background

I started life, and I remain at heart, a field naturalist. See FFON website.

When my father returned to Britain after the Second World War, he regaled me with stories of his time in India, Burma and Ceylon. He told me about large moths and other insects attracted to searchlights and snakes and crocodiles. He described time spent with his Indian troops and taught me some words in Urdu. He took me out on the Essex Marshes looking for newts and fish and we collected caterpillars that we reared to moths. These animals had to share the balcony of my parents’ top-floor flat with a washing line and sundry domestic items.

When I was six, the family moved to a small semi-detached house in Thorpe Bay, Essex. This had a small garden! I continued to catch and keep local animals, ranging from hawk moth larvae to grass snakes, and I read avidly all I could about them.

In 1955 I joined the local Scouts and I decided almost immediately to study for my Woodcraftsman Badge, the junior version of the Naturalist’s Badge. This required me to keep a natural history diary for three months and to record in it the birds, butterflies and trees that I saw during that period. I passed the test, was awarded my badge (I still have it) and decided to continue writing the diary. I still do so, 65 years later.

Professional details – a team effort

I am part of a husband and wife team. My wife, Margaret E Cooper, is a non-practising lawyer (solicitor of the Supreme Court) who has special interests in animal and conservation law and is known to a number of members of the Guild. She works as a free-lance writer and consultant and lectures at various universities, particularly at post-graduate level, on legal and allied matters. She was a member of the UK’s Farm Animal Welfare Council (FAWC) and (1999) the Zoo Standards Review team and author (two jointly) of three books and many papers on animal and conservation law.

Living and working overseas

In August 1966, after graduating in veterinary science (and three years before Margaret and I were married,) I went to Tanzania in East Africa to work as a Veterinary Officer under the Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO) scheme. I was in the possibly unenviable position of being the first veterinary surgeon to serve overseas as a “volunteer” but my year there was a wonderful, valuable, experience and changed the course of my life.

Since 1969 Margaret and I have spent approximately twenty years overseas - in Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Trinidad and Tobago, France and Germany. Our time in Africa included nearly two years directing the Centre Vétérinaire des Volcans in Rwanda where we were looking after the health of the famous mountain gorillas. In 2009 we returned to Britain from nearly seven years at the University of the West Indies in Trinidad and Tobago. There we combined our medical and legal backgrounds in the promotion of an interdisciplinary approach to veterinary and biological education, tropical medicine, wildlife conservation and forensic science (see later).

Career choices

My early years as a veterinary officer in East Africa had a profound effect on my subsequent professional training in Britain. Both in Tanzania and in Kenya I had often found myself working with medical colleagues and practising what is now termed “One Health”. This was stimulating and fun. I realised then that it should be possible to combine my passion for natural history and wildlife with my training as a veterinary surgeon and thereby turn myself into a comparative pathologist.

I decided therefore to work towards Membership of the Royal College of Pathologists. On our return to Britain in 1974 I joined the Medical Research Council. I then undertook training in toxicological pathology at a commercial laboratory. For an eventful 13 years (1978-91) I held a unique position as Senior Lecturer in Comparative Pathology and Veterinary Conservator at the Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS). There I met Bari Logan, the college’s Prosector, and we quickly realised that we shared many interests, ranging from wildlife and dissection to the life and work of Charles Waterton, the English naturalist and explorer, a skilled taxidermist who preserved many of the animals he collected on expeditions.

As Bari has said on this (Guild) website “The College was amazing” and he and I were able to involve ourselves in many activities there relating to live and dead animals – and to humans. I already knew a number of taxidermists (since my youth I had tried to prepare dead animals myself before realising that trained taxidermists knew better!) but Bari put my understanding of their skills on to a new footing. Bari had been a Founder Member of the Guild of Taxidermists in 1976 (I understand that I too attended that meeting!) and, by the time I arrived at the RCS, was a Committee Member; he became Chairman in 1980. Bari and his colleagues in the Guild invited me to lecture on such topics as zoonoses and they consulted us both (Margaret and me) on diverse issues.

During this same period I got to know other taxidermists, amongst them Dr Pat Morris, then Senior Lecturer in Zoology at Royal Holloway College, University of London. We published together on parasites of hedgehogs and were fellow Directors of the International Summer School on the Breeding and Conservation of Endangered species, based at Jersey Zoo (JWPT). He and his equally eminent wife Mary are also keen supporters of the Linnean Society (a Fellow) and of the Camberley Natural History Society which was founded in 1946 by my schoolboy mentor Maxwell Knight (1900-1968), naturalist and broadcaster but also an outstanding British spymaster, reputedly the model for the James Bond character "M". See FFON.

After spells overseas again in Tanzania, Rwanda, the UAE, Trinidad and Tobago (T&T), France and Germany, I retired from full-time academic work (teaching and research) and Margaret and I returned from T&T to Britain. I had served there as Professor of Pathology in the School of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of the West Indies (UWI), from 2002-2009.

Back in Britain

Now based again in the UK, Margaret and I are involved in teaching at various universities and pursuing our professional interests, especially in animal law and forensics. We have played a part in the development of veterinary forensic medicine, culminating in two books on the subject (2007 and 2013); this conveniently combines our legal and pathology interests and also has links with East Africa because of the growing threat of wildlife crime.

When not in “lockdown” on account of Covid-19, we continue overseas travel and lecturing, including work with wildlife, domesticated animals and communities in East Africa. Most of this is on a voluntary, unpaid, basis. We believe that at this stage of our careers, after spending nearly two decades living and working overseas, we still have something to offer the poorer, less “developed”, parts of the world. People often ask us why we continue to do our voluntary teaching. The answer is probably in the maxim “Anayekupandia chakula ni bora kuliko anayekupikia chakula” (Swahili Proverb. One who teaches you to plant is preferable to one who gives you food).

Nowadays, although a chunk of our hearts remains in Africa, we have to admit that we are based in Britain, in Norfolk. We are involved in local issues, especially natural history, and active in such national and international concerns as human rights. We use our rural home as a springboard for our overseas activities. We do not own a car, either in Britain or Africa, preferring to use public transport and thereby channelling the savings into our overseas voluntary work. We also like to think that it helps protect the environment.

Conclusions

Margaret and I consider ourselves very fortunate. We are still married. We have two grown-up children and three grandchildren and we have friends of different races and creeds in many parts of the world. We still believe that we can contribute something to needy communities and, despite the many threats to the planet, we remain optimistic about the future.

Closing remarks

Margaret and I have been involved with the Guild and its members – and with taxidermists in other countries - for many over four decades. We regularly publicise the Guild in our lectures and writings - see below, for example, taken from our 2007 book about veterinary forensic medicine:

“Taxidermy (the art of preparing, preserving and mounting the skin of animals) has a long and often distinguished history. Professional taxidermists are responsible people with an interest in natural history, conservation and education – for example, members of the Guild of Taxidermists in Britain. Such people only accept specimens that have been legally obtained, they keep proper records and they have an enforceable code of practice”.

In conclusion, it is a pleasure to count so many taxidermists amongst my friends. Margaret and I thank them for helping to open the eyes of the public to the beauty of the natural world and we compliment the Guild of Taxidermists on all they have achieved over the past 44 years. We send best wishes to the Guild and, in so doing, remember those colleagues who are no longer with us.

I express my heartfelt thanks my wife for advising and commenting on this text and for her support over many decades. Asante sana, Margaret!

John E. Cooper

2nd July 2020

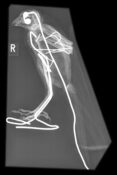

Below are radiographs of a lanner falcon and a crocodile that John and Margaret use in their lectures to students about wildlife forensics. They explain that a good radiograph show how the taxidermist mounted the bird, may indicate who the taxidermist was and the croc's well-formed bones.

John Cooper and Gordon Hull looking at the skeletal remains of "Guy", the famous lowland gorilla that lived at London Zoo from 1947 until 1978.

This was part of a study that led to the production of a book by John Cooper and Gordon Hull, "Gorilla Pathology and Health with a Catalogue of Preserved Materials" (Academic Press, 2017).