DON SHARP

(9 April 1942 to 7 May 2004)

Shortly before he died in 2004, Don Sharp wrote an autobiographical memoir of which this is a transcription. Spellings have been corrected, but nothing else.

Born to be a Taxidermist

I was born in Luton Bedfordshire at 56 Walcott Avenue on the 9th April 1942, mother Flora Christina McDonald, father Horace Sydney Sharp. It was during the second world war that I was introduced to animal husbandry. Father kept sheds full of Dutch rabbits and a few hens for eggs. Of course times were hard and the rabbits ended up as meat during the food shortages of the war. I remember well when very young gathering food for the livestock scything down stinging nettles and sun drying them for winter fodder. We also kept pigeons for meat and father maintained two allotments and a vegetable garden.

I lived my early boyhood years in Luton Bedfordshire. I enjoyed the easy access to the magnificent Chiltern hills, River Ouse, the downlands, Whipsnade Zoo and the fine landscape around Stopsley, Hitchin, Lilly and Kings Walden.

For as long as I can remember I have been fascinated with wildlife and the countryside, feeling myself bonded to the fields, woods and rivers. The massive stately beech trees of the chalk downs impressed me so much. Wildflowers of the hills such as orchids and cowslips grew in vast waves; hedgerows were very large and bushy. Wildlife was abundant. Unlike most boys, I was never interested in what they call sport. I was however contented to just roam the countryside in search of natural history subjects.

When only five years of age, in 1947, my mother worked from home for a Luton hat factory. Every week, large sacks of feathers came to the house for sorting and arranging for hats. Feathers of different colours, shapes and sizes, cape skins of Golden, Reeve’s and Amherst pheasants were laid out on the table top for arrangement. I was indeed captivated by the marvellous colours and patterns of each feather. I feel sure that being in contact with skins from such an early age gave me a fascination for fur and feather.

From a very early age I have always had live creatures around me, from frogs, toads, newts, sloworms to white mice and many more. My bedroom also functioned as a museum with fossils, butterflies, bird eggs and nests. There were also several cases of stuffed birds picked up cheap from antique shops. However I eventually dismantled them to find out how they were stuffed. I can also remember that when very young, possibly at the age of seven years, making cages for mice out of wooden fruit boxes obtained from local shops. My first mice were very handsome black eyed creams, creams and pink eyed whites.

My childhood was totally spent exploring the Bedfordshire countryside fishing and keeping live animals. Many hours were spent at disused clay pits and ponds at Stopsley, catching great crested newts and smooth newts with a worm on a length of string. I became very skilled at finding bird nests, harvest mice, voles and grass snakes.

I was indeed very pleased to live within cycling distance of the famous Lord Rothschild Museum at Tring, Whipsnade Zoo, Woburn Park and Ashridge Forest (famous for Glis glis). Lord Rothschild was one of the greatest naturalists of our times. Often I would cycle 15 miles to the zoological museum at Tring, spending many enjoyable hours looking and studying the magnificent mounts of birds and mammals. I was intrigued by the way these mounted animals looked so lifelike. Also regular visits to the Natural History Museum, South Kensington (when it was a museum simply packed with mounted animals). During one of my many visits to this establishment, I purchased a small red booklet published by the museum about collecting and skinning birds. I was only ten years of age but I read that little booklet over and over again until I knew the process of skinning a bird. One day, I found a dead blackbird by the roadside. I took it home cupped in both hands like a precious gemstone; I was so excited about my find. Armed with my father’s razor blade, borax and the little instruction book I set to work. Everything went well and in due course, the bird was skinned and stuffed with cotton wool and supported by thin wires. It was my first specimen. I was so pleased. To me the blackbird looked very real. After producing my first mount more dead creatures came my way: a grey squirrel, hedgehog, starling, rabbit and a fox. I was indeed on my way to becoming a taxidermist. Also many injured creatures came into my hands from neighbours, friends and school pals. Owls, thrushes, blackbirds, pigeons and even a badger cub. These were treated and fed and eventually released back to the wild.

Perhaps I was a bit of a loner, preferring to ramble through the fields and woods in my quest for wildlife knowledge. However at the age of 11, I had an unfortunate accident. I was severely burned after being trapped in a straw fire. Both legs, neck and arms took the full force of the flames. The next ten months were spent in hospital going through painful skin grafting operations. Unfortunately I missed about 12 months of schoolwork finding it very difficult to catch up the lost time. Classes were large and teachers were not prepared to help individuals. School days were not happy days. However, my time in hospital and convalescing gave me a lot of time to read books about wildlife and drawing animals. My favourite magazine was one called the gamekeeper and countryside. I studied these from cover to cover, reading every article. I gained a tremendous amount of knowledge about British wildlife amongst these pages.

During my illness, Uncle John (mother’s brother) bought me a book about animals and also presented me with a fresh pheasant’s egg. I can still picture the amazing rich brown/olive colour of this egg, smooth and shiny, quite heavy for its size; it was still full of its contents. However, Uncle John skilfully showed me the blowing techniques, taking out the contents through just one hole using a pin and a piece of hollow straw.

Returning to school after a long period of sickness was indeed very difficult and I could not catch up with the lessons I missed. In the science room at school there were four long cold water aquariums, each occupied with fish - bitterling, stickleback, minnows and catfish. I’ve often spent a long time looking into these underwater scenes. In a short time I was made aquarium monitor. The science master, Mr. Brown, encouraged me to establish a small school museum after seeing some of my mounted animals. The thought of setting up and maintaining a real school museum appealed to me. Also it would mean I could skip a few lessons. Word soon got around the school that I wanted natural history items and soon I was handed numerous objects - dead birds, skulls, wings, nests, fossils and one or two live creatures.

At home I had a multitude of animals: grass snakes, slowworms, newts, budgerigars, fish, tortoises, mice and hamsters. I remember well obtaining rare, coloured hamsters from P. Parslow. On one occasion one of my best female hamsters went to school with me in my pocket. I was proud of this particular creature. In those days, hamsters were unusual pets. The hamster was placed in my overcoat pocket for safekeeping and as usual it just curled up and went to sleep. However when I went to get my coat at 4pm, no hamster could be found. After frantically searching the cloak room for a good hour, I went home very upset. The next day I hung my coat on the same peg and went to the classroom. On returning to my coat in the afternoon, I found the hamster asleep in the same pocket.

I swapped a mouse for a baby tawny owl. One of my classmates brought the owl and put it on the back of a chair during the lesson. I was upset because this boy had no idea how to feed it. He was trying to feed it worms and slugs.

I remember well when I was 14½ years of age and thinking about a job when I left school. Of course I wanted to be a skilled taxidermist. I asked Mr. Brown who I should write to in order to receive first-class training. In those days, taxidermists were few and far between. The next day Mr. Brown gave me two addresses to write to: Rowland Wards, Piccadilly, London, and Edward Gerrard’s and Sons, Natural History Studios, 61 College Place, Camden Town, also in London. I liked the sound of Gerrard’s natural history studios and wrote to Mr. Edward Gerrard to see if I could be an apprentice. A few days later, I received a very nice letter from Mr. Charles Gerrard inviting me down to Camden Town for an interview and asking if I would bring a selection of my own work with me. The following week I packed some of my best specimens into a box: a hedgehog, fox head, squirrel, blackbird and a fish. I was very nervous and visualised a large firm with 50 people working away. However, this image was totally wrong.

I got on a train at Luton station with two cardboard boxes, one under each arm. The journey was about 35 miles and took 1¼ hours. The train stopped at every station, Harpenden, St Albans, Radlett, Borham Wood, Kentish town and St Pancras. The journey seemed endless. All the time I was wondering what this taxidermy firm was like. Anyway I got off at St Pancras and following Mr. Gerrard’s instructions, I made my way to Camden Town. I passed the Royal Veterinary College at College Place and turned the corner to find an archway in a very old brick wall. Above the culture was a half moon sign on which was the name Edward Gerrard and Sons, Natural History Studios, 61 College Place. I walked through this arch and down a long alleyway. There I came to a courtyard with very old Victorian workshops on each side. I was confronted by a lady who was then the secretary. She then took me into a very large showroom. I just stood in amazement. There were mounted polar bears, elephant heads, ostrich, wolves and dogs. It was like heaven to me. My knees were knocking. Just then the door opened and there stood a man with a stern face, but with a smile. He looked old to me at the time. He must have been in his late ‘50s or early ‘60s. This was Charles Gerrard. He said he was pleased I could make it and thanked me for writing to him. He was straight to the point and asked what I had got in the boxes. I opened each box and placed the contents on a nearby table. Mr. Gerrard just took one look at them stood back and said "when can you start my lad?" I explained that I’m not quite 15 yet and I have got a few more months at school. "Well", he said, "as soon as you leave school you can come down here to work and serve an apprenticeship". He then began to show me around the workshops. We crossed the courtyard and went through a large black door into what he called his school, a small room with a stove in the middle of the floor. There stood his son, Dick Gerrard, who was working on a fox head. We went across the courtyard again into another room. This was a very long room with four people working. Horace Owens, George Kent, Bill (?) Burrier and Mr. Green. It is incredible but I can remember every word spoken and even the smell of camphor and phenol, yet it must be 35 years ago [actually nearly 50!]. I started my apprenticeship on the fifth of February 1957. I got up at 5:30am to catch the 6.30 train from Luton. This got into St Pancras station at 7.40. A brisk walk got me to the studios at 8:00.

Ted Gerrard and showroom c1950

My first job at Gerrards was quite a surprise. I was expecting to be given ?? to start with. However Charles Gerrard presented me with a beautiful little egret which was snowy white. I didn’t realise he had so much faith in me. I remember the first day very clearly. I was skinning the egret, Charles was mounting a pair of crossbills and Dick was mounting wood pigeon for the Royal Show. After the first day’s work, I was given all kinds of work - fox heads by the score, fish and numerous birds.

I was only 14¾ years of age when I started my apprenticeship with Charles Gerrard. On my first day, I was told by Mr. Gerrard to make a workbench for myself. This I did in two days. It measured 8’ x 4’. On my third day, Charles gave me a beautiful little egret to skin and mount. In those days the birds were washed in soap powder and water, degreased in benzolene, dusted with magnesium carbonate. With a thin cane, the mag carb was tapped out of the skin. The skin was then painted with arsenic based soap preservative. My taxidermy went from strength to strength under the expert supervision of Mr. Gerrard. I shared a workroom with Charles and his son Dick Gerrard. Across the yard was a very large workshop occupied by four outstanding taxidermists - Horace Owen, Bill Dwyer, George Kent and a Mr. Green. I was nervous walking through this room as very few words came from the mouths of these craftsmen. Over the years however, a few secrets were passed on to me.

In those days of course there were no deep freezers. I am talking about 1956 now. All the birds were skinned and mounted when freshly brought in. The mammals were skinned quickly and the skins placed into large vats of fixative solutions - water, alum, salt and carbolic acid. Often they were left in the solution for a few days, taken out and hung up to dry. When needed, they were put into clean water to relax. I am still amazed how they quickly reverted to a natural suppleness.

Edward Gerrard, Charles’ brother, was in charge of all the accounts and business. He also ran the hire side. Hundreds of animals were loaned out each month for film, theatre and props. Steptoe and sons program directors always were around choosing props.

The years rolled on. I was often sent to Regents Park Zoo, to skin either a bear, camel, bison or lion. I had to walk from Camden Town to the Zoo with an empty barrow, skin the creatures in the zoo prosectorium and return with the barrow full of skins, bones and skulls, often dripping blood along the street (can you imagine doing this nowadays?). It was very hard graft, non-stop taxidermy. Skinning and mounting, bone scraping, foxes, badger and otter heads galore, fish of all kinds, case building, fish and paring large skins (bloody hard work). However it did me no harm; I was so keen to learn the art of taxidermy. Certain things stick in my mind about working at Gerrards. One was seeing Charles Gerrard mount a pair of crossbills. I thought they were immaculate. The other is hearing Charles sing [not clear what]. Fine memories nobody can take them away from me.

Several things happened in the early ‘60s that changed my apprenticeship. Charles Gerrard developed a heart problem, the redevelopment of Camden Town and the new wildlife and importation laws. These led to the final closure of a long established taxidermy firm.

I found employment in Luton repairing brass band instruments. Again it was a small family firm, Philpots and Sons, musical instrument makers. My job included repairing damaged instruments knocking dents out of brass units, silver plating and renovating. Although I did not work with natural history, all my spare time was taken up by doing taxidermy commission work. One customer offered to set me up in business. I also applied to go to Kenya to work in taxidermy. However there was Mau Mau trouble at the time and white men were being knocked off. After two years with Philpot’s, I left and joined the conveyer belt at Vauxhall motors, welding cars and sweating blood. I joined the museum association with a view to work in a museum. The taxidermy jobs then were all taken and I think by old men who keep a low profile. However in 1966, I applied for a taxidermist position at Wollaton Hall Natural History Museum.

The position of taxidermist/preparator was given to me. I was so proud to be part of a museum team and working in a natural history museum. The curator then was Mr. Cyril Halton, a very strict and museum man. My job at Wollaton consisted of taxidermy display and conservation. I was left alone to display British wildlife in natural habitat groups painting backgrounds and wax foliage making. I also produced taxidermy for the East Midlands Museum Services. For the first two years, I stayed in the YMCA hostel in the middle of Nottingham. I often worked in the museum at weekends. Unfortunately in those days, taxidermists kept themselves to themselves and were reluctant to meet their own kind.

However in 1976 …… [this presumably went on to describe formation of the Guild of Taxidermists, in which Don played a leading role, but subsequent pages are missing. Two other pages add the following paragraphs].

I have organised many [Guild] conferences over the years and Nottingham has become one of the main centres of taxidermy in the UK. Yearly conferences are held in Nottingham for taxidermists. Many overseas technicians and taxidermists visit Nottingham to attend these conferences. We have had visitors from Switzerland, France, Malta, Gibraltar, America, Denmark, Sweden, Germany and Norway.

Taxidermy is I suppose an act of homage. Preserving wildlife is one way of showing respect for animals. Visual art for me is a well-mounted and artistically presented creature. Respect for nature is for me to save a creature that would otherwise decompose.

If I am cremated I wish that my remains will be taken to Abbott filled into a share and buried bile pate at (?) Aryoinack. Money will be used from my bank account. I have to my very best, helped people throughout my life and helped the wildlife around us. My final farewell to all my friends and to the people who admire my life’s work.

Gallery of Some Work

Lectures

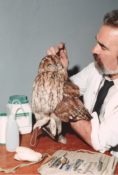

TRADITIONAL TECHNIQUES ON MOUNTING A TAWNY OWL - Don showing his techniques for mounting a tawny owl using traditional bind-up and sliding wire. He also showed casting and moulding for the fence post that he sat the bird on.

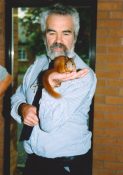

MAMMAL HEAD FORMS - Don gave a demonstration on making head forms for a mammal at the conference in 1996. See No. 27 of the Taxidermist Journal in 1996/1997 for the full article.