PAT MORRIS

What/Who inspired your interest in taxidermy?

As a kid, I lived in the East End of London where the only animals to be seen were in the local museum. When it closed down, I pleaded with my mother to get me a stuffed bird. She brought home a Ptarmigan in winter plumage that I couldn’t identify. I got my father to take me to the Natural History Museum to find out what it was. I bought my first bird, an Indian roller, for an entire month’s pocket money when I was about 10. My first squirrel cost sixpence, less than the price of the glue I needed to stick its fur back in place.

When did you start and what was the first item you worked on?

I borrowed all the old books I could get via my local library and learnt how taxidermy was done. I was about 15 when I tried it for myself, crudely stuffing a few squirrels that I had shot with my catapult. I was given a pinioned female Eider duck by a man who owned a private zoo and I set it up to his satisfaction, complete with part of a pigeon’s wing suitably coloured with boot polish to match the duck’s plumage. I got better at taxidermy, although I never enjoyed the benefits of having someone to teach me. During my schoolboy days and into the 1960s, I collected old taxidermy when I could afford to do so. For a while my most expensive bird was a hoopoe in a glass dome costing 10 shillings. Later as a student, I had a grant and managed to buy a passenger pigeon for £100. My collection of historical taxidermy now features the work of about 150 British taxidermists and includes lots of associated documents and paperwork, plus copies of all the books ever published in Britain on the subject. In effect, it forms the national archive and will one day finish up with the Booth Museum in Brighton.

What was your first break into the industry?

I have never sold any of my own taxidermy and in fact have spent more time building and renovating old glass cases which I sold in order to raise the money to buy better things. This way, I learned a lot about how the old taxidermists worked, creating decorative ground work for example. I also began to prepare mammal study skins for teaching purposes, helping me to give lectures and run courses that earned money to supplement my student grant. This led to collecting mammal specimens for the Natural History Museum in London, effectively financing travels to France, East Africa, New Guinea and 5 visits to Ethiopia. By the time I was 30, I must have skinned several thousand small mammals and a few larger ones.

Work History?

After finishing my PhD on hedgehogs in 1968, I was appointed to the academic staff of Royal Holloway College (University of London), where I remained for the rest of my career. It was my actual job to teach vertebrate zoology and a range of other subjects. My interest in taxidermy was viewed with disdain and in 40 years at the College, I only ever gave one lecture on the subject. I published many papers, magazine articles and natural history books and retired early in 2003 to spend more time with my taxidermy. I have never been a practising taxidermist, my interest is in the history of the subject, although my fairly extensive practical experience has made me very familiar with working on dead animals of many kinds, ranging from squids and fish to birds, mammals, snakes, frogs and a couple of crocodiles.

Notable Projects?

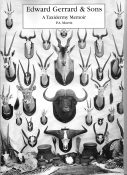

After I retired, I bought the necessary software and began to produce a series of books on aspects of the history of taxidermy to be privately published by myself because no commercial publisher was willing to get involved. This was despite the fact that I had collaborated with many publishers to produce natural history books that have sold more than a quarter of a million copies, not to mention umpteen magazines. I could do the job, but nobody could see any benefit in publishing on this subject, which actually was seriously out of favour with the public for a very long time. My first taxidermy book was about Rowland Ward and the business that he formed. I was helped by a number of generous ex-employees. The book sold well enough to support another, about Gerrards the London taxidermists. I went on to do one with a few colour plates, describing the work of the Van Ingen factory in India, which had 150 staff at one time. Their work is of high quality and common in the antiques trade. I made 5 visits to the old factory, now destroyed, and was able to copy the firm’s records, listing 54,000 jobs, including 20,000 tigers and 23,000 leopards. My book sold well enough to finance a smaller one (about Hutchings of Aberystwyth) that was all-colour and led to one about Walter Potter and his famous anthropomorphic animal groups. This has now run to 3 different editions and (amazingly) has gone down well in America. Two more books followed (one on the famous eccentric Victorian naturalist, Charles Waterton, and his creative taxidermy, another was about my own collection and taxidermy dealers). In 2010, I published my ‘History of Taxidermy - art, science and bad taste’. It’s 400 pages, with 1,000 illustrations, including coverage of the Guild of Taxidermists. People ask how long it took to write and the answer is two years to produce, but 50 years to gather the information and pictures because so much of our taxidermy history has been lost in the past.

Who inspired you the most when you were learning?

My parents always supported me in full, no matter how bizarre my interests appeared to be. My wife, Mary, has also been a steadfast supporter, well-known to many Guild members for regular attendance at meetings. She has traipsed around the world, visiting more museums and their storerooms than anyone else I know.

Who inspires you the most now or is it just Mother Nature?

Mostly Mother Nature, but I learned a lot from my association with staff of the National Trust. I have been much impressed by the work of Guild members, notably Peter Summers, James Dickinson, Mike Gadd and others. Their craftmanship is admirable as is their willingness to share and to teach. But I have also admired the careful observation and attention to detail shown by many others who lack formal academic qualifications, but whose dedication would put most of my former university students to shame.

Have you helped or taught any successful students?

Yes, I taught hundreds of them. What they actually learned I cannot say, but some have developed successful careers following similar paths to my own.

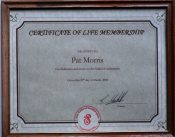

Guild Qualifications

I was made the first Honorary Life Member of the Guild. I’m actually very proud of that. Taxidermy was never my job, so to gain recognition from the professionals in their own field means a lot to me (especially as the professionals in my real-life profession never offered recognition for what I achieved in the field of zoology, despite its success in many forms). In 2017, the Queen awarded me the MBE “for services to the natural and historic environment”. The historic bit was in recognition of my efforts to document the history of taxidermy and, in particular, sort out the taxidermy in the National Trust’s collections database.

Guild Committee Work

I was a member of the Guild’s Committee for a few years, as its Newsletter Editor, but I avoided further commitment. I feel the Guild should be run by its practitioners in whatever way they see fit. Anyway, I was always too busy with my voluntary job as Chairman of the Mammal Society.

Pat giving one of his numerous lectures at conference in 2008

Lectures

Lectures are what I do! My University job meant giving lots of them and I gave (and still give) talks to local natural history societies and the like, sometimes even about taxidermy. I have given an annual lecture for the Guild for about 40 years.

Judging

I have only once acted as a taxidermy judge. My judgement did not meet with universal acclaim because I come to this subject from a different direction. I have only once entered one of my specimens in a competition. It was when I was at school. I gained no prizes for my former pet rook, just derision.

Gallery of Work

I refrain from showing my own embarrassing efforts at taxidermy. Anyone who needs to know more can see some of it in my book, “Me and my taxidermy- a personal memoir”, published in 2016.

Pat Morris, 2020